2016 TRIUMPH BONNEVILLE T120 – THE LEGEND RETURNS…PROPERLY

Once upon a time, the Triumph Bonneville T120 was the greatest motorcycle in the world.

Named after the legendary prehistoric salt lake in Utah used to set World Land Speed records, the Bonny has carved its name into the bedrock of motorcycle history.

In 1959, when Triumph took its single-carbed Tiger and whacked another Amal on it, the Bonneville became THE British bike to own and ride.

This was what it looked like in 1959.

This is the 1969 incarnation.

Forty-seven years later, it’s back and it’s finally beautiful.

The ‘120’ in its name stood for its top speed in miles per hour, and back in those days, 120mph (193km/h) was a pretty big deal. Sure it had its issues. What British bike of that era didn’t? But it’s only in retrospect that we see these issues. Back in those days, smoking electrics, pockets full of spanners, and total-loss oil systems were perfectly normal.

And it was a time when Britain truly ruled the motorcycle world in terms of performance, with the Bonneville pretty much at the top of the heap.

But not only did it go, it was also quite one of the most aesthetically beautiful bikes people had ever seen. To this day, its petrol tank is the metallic embodiment of perfection, with a flowing purity of line that has often been imitated, but never quite replicated.

This is one of the early tanks – as close to physical perfection as ever came out of England.

And this is today’s jobby. All 14.5litres of it. Not too shabby at all, I reckon. And it won’t rust or spring leaks.

You cannot look at this and tell me it’s not beautiful

I bought a 1979 Tiger (I couldn’t afford the twin-carbed Bonneville) and loved it like a mental patient adores his straightjacket. It comforted me, exalted me and tortured me simultaneously, which is what a great bike does to its owner.

Outlaws rode them, cops rode them, and even after the Japanese started building relatively more reliable rocketships in the early Seventies, the Bonneville was still where everything cool was at.

The ‘last’ Bonneville came out of Meriden in 1983, when the factory closed, and that was, apparently that. But a fellow named John Bloor acquired Triumph, and licenced a company called Racing Spares to keep on keepin’ on.

Racing Spares was run by Les Harris, who came to be known as the “Saviour of the British Bike Industry”. Les continued to make Bonnies (known as Devon Bonnevilles because they were made in Devon and not out of devon) and finally managed to get them out to an indifferent market in 1985, until production ceased in 1988.

That road probably hasn’t been resurfaced since 1969.

The Amberlight Cafe gave us a warm welcome and good coffee. I’m outside reminiscing with Peter Thoeming about 1969, when he was 50 years old.

The slate grey Black was my next favourite colour scheme.

But John Bloor persevered. In 2001, the Bonneville 800 appeared. From then until 2015, the Bonneville appeared each year with a slightly bigger engine (topping out at 865cc) and eventually fuel injection, but it was no longer the king of the performance castle.

That mantle had long since passed to the Japanese.

And to be honest, it was not the best bike Triumph was producing – either in terms of aesthetics or performance.

The great Bonneville name had been diluted. Sure, it was a better bike in every way than the Harley-Davidson 883 Sportser it competed with, but it just wasn’t what people – and certainly me – seemed to want in and from a Bonneville.

And so we come to 2016 and the all-new Bonneville T120 – and it is obvious that Mr Bloor has decided the Bonneville name shall no longer languish in the memories of old men with crazy eyes.

It comes with a daytime LED running light, so your headlight is not on all the time.

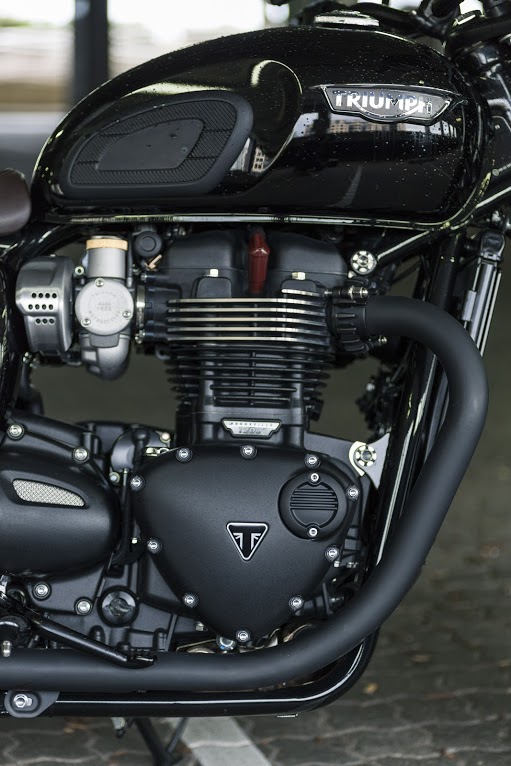

The Black is wondrously black.

Even its bottom is now black.

For 2016 Triumph has created the most beautiful and effective Bonneville of the modern Hinckley era.

And it invited me to come to the Barossa Valley and wring its ever-so-pretty 1200cc neck for two days.

As it turned out, South Australia dished up all the weather it had in two days, and I rode pretty much every road worth riding in that part of the world. It was a most comprehensive bike test, in every sense of the word.

We did everything from flat-out speed runs (it tops out at a shade under a genuine GPS-backed 200km/h) to the treachery of a leaf-and-gravel-strewn Adelaide Hills, as well as some gloriously dry, fast and sweeping stuff around the Barossa. We even managed to spend a few hell-crazy hours at the Collingrove Hill Climb track, but I’ll get to that in a sec.

The 2016 Bonneville was measured, tested hard, and not found wanting. It was sure-footed when it needed to be (and it needed to be a lot), and hooligan-friendly when the guns were drawn.

Now that’s some sexy alloy.

The “I can’t believe they’re not carbies!” fuel injection. Made to look like the old Amals, right down to the brass thingy on top.

The narrowest radiator in the business. To which I would fit a radiator guard. That front wheel tosses up some shit.

Gone was the pootling and waffling sub-litre Bonneville donk of 2015. In its place is an engine, physically no larger than the previous model that produces a massive 54 per cent more torque – 105Nm at 3100rpm (and redlining at 7000rpm).

The new Bonneville also boasts a slick-shifting new six-speed gearbox – with sixth being a true overdrive cog, and a range of modern electrical and mechanical beautnesses. It comes with two rider modes, a new swingarm, traction control, ABS, a slip-assist clutch, ride-by-wire throttle, immobiliser, and a USB charging socket under the seat. It even has heated grips, but you need to be on the verge of ice-death to turn them on High – because High is truly High.

The new engine now fires at 270-degree intervals, which has reduced the vibration inherent in the previous model and made the Bonneville a much smoother and far more engaging ride.

And it is, as I have said, a true vision splendid. It is both more elegant and brawnier-looking than the previous model.

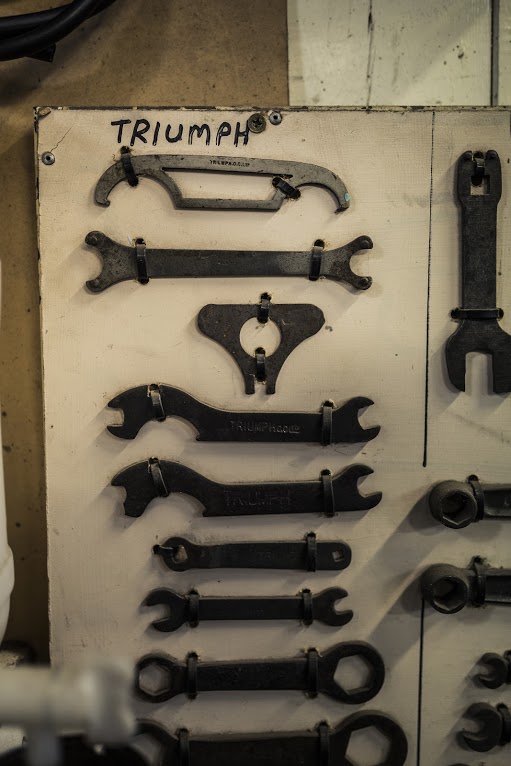

The wondrous Bill’s Bits and Bikes in Birdwood.

Great things lurk within.

Little boxes full of goodies.

Old iron is great iron.

Where does one sign?

Tools from the Mines of Moria.

If you’re ever in Birdwood, do go and visit this place.

Triumph has gone to great lengths, not only to make it look a lot like a 1969 Bonny but also to ensure its build-level was of a much higher standard than on previous models. The cosmetics – the anodised aluminium covers, the exhaust pipes, the nuts and bolts and the myriad little embellishments are all top-notch. Hell, even the key is nicer and more substantial. And great strides have been made to tidy the bike up – the catalytic converter has been hidden, the radiator is the slimmest I’ve seen, the hoses have been neatened up and the headlight and gauges have been brought closer together for a cleaner silhouette.

It was immediately obvious, as we headed out of Adelaide, that the new Bonneville was indeed new. It felt immediately ‘righter’ and the engine was a revelation.

We were an eclectic group – led by the intrepidly rapid and skilled Nigel Harvey from Triumph, the blisteringly fast Paul Young, the almost as blisteringly fast Nigel Crowley and the always dashing and also blisteringly fast Trevor ‘Fawn Horn’ Hedge. Then there was me, and somewhere far behind me were a brace of happy hipsters, one of whom crashed at the first photo-stop, which doubtlessly contributed to the authenticity of his riding experience.

Hedgie creatively interpreting the feel of the vibe of the thing.

Nigel Harvey – swamp thing, you make our hearts sing.

I’m off to ride The Wall.

Look at the banking on the thing.

Mr Crowley was kind enough to let me lead.

Right then. Off to the nearest vineyard…

…to borrow some grapes.

We rode a series of gorges and ranges, on an often uncertain surface, and I learned that these new Pirelli Phantoms were orders of magnitude better than the Pirelli Phantoms of the eighties. There were times the traction control and ABS stepped in to assist me in my travels, but I blame the road-surface for my misdeeds on the throttle. Ground clearance was better than I expected, and normal people will keep their hero-knobs shiny and unmarked. I left bits of mine in South Australia, which was right and proper when trying to keep up with the frenzied bollocks ahead of me.

Lunch was in Lobenthal and it looked as if the weather was clearing up, so I was confident I’d get to explore the business end of the speedo after my souvlaki.

I got everything I wished for and more, when we stopped at the Collingrove Hill Climb track.

“Do not die here,” Nigel said, as I whooped and yodelled like a lunatic. “It would be really bad for me if you died here.”

Fair point, I felt, as I wheelspun up hill off the start line, determined not to perish, and two short corners later beheld The Wall.

“Oh this is serious,” I muttered to myself.

Simple and stylish.

Also simple, but not so stylish. Me, I mean. Not the Bonneville.

Cliffs. Water. Triumphs. Crowley. And weeds.

The Wall is a breath-stopping, fully-banked, uphill right-hander that looks like something out of a video game. I have no idea how they got the bitumen to stay on that hillside, and after I had ridden it a few times I still had no idea. But I did not care. It was other-world special, even under instructions not to die.

Nigel then fed us iced donuts to make us even crazier, and we sat out a brief but solid rainstorm in the comfort of the clubhouse. Then there was some interpretive dance-riding by the tan-coloured performer formerly known as Hedgie, after which we all rode to a nice hotel buzzing on sugar and speed-fever.

Dinner was spectacular. The Appellation at The Louise, pilgrims. Try it out. If you take a date, you’re gonna get lucky, for sure. I do remember drinking vast quantities of superb wine, and celebrating my near-death hill climb experiences earlier that day. Nigel had said nothing about “almost dying”, so that was the zone I operated in.

The next morning it was grey, foggy and raining.

So we splashed in puddles for a bit and headed for Kyneton and the descent into Sedan.

If you stand on the top of the Sedan Hill Road as it descends into the outback, you’ll notice two things.

Australia is a very big place and most of it is dead flat, is the first.

The second is that while it may be pissing down in the Barossa, the rain rarely makes it past the hill you’re standing on because the gale-force wind encountering the wall of outback climate causes it to disappear.

Which is just what one wants if one desires, theoretically, to see just how fast one’s motorcycle goes.

I am, of course, confessing to nothing. Even if I was to stand shackled before a jury of my peers, I will admit to no crime. Because I committed no crime.

I just rode a Bonneville on an empty road at a speed I judged to be safe and in keeping with all the laws of humanity and decency.

It was like the 70s all over again.

You’d think it was 1972.

The rain behind me was soon not behind me.

Lunch was sunny and delicious and taken upon the deck of the marvelous old Swan Reach hotel, which stands on the banks of the Murray River like a bulwark against the vastness of the outback.

Our videographer, Boy Band, made several attempts to force the galahs in the giant river gums on the opposite bank onto a war footing with his video drone. And he was on the verge of success when I told him there were two National Parks rangers eating lunch and watching him just inside the dining room.

After lunch, we followed the Murray to Walker Flat where we crossed over the river again, and battled a vicious headwind back up into the hills and Mt Pleasant.

My fuel economy was affected by the head-wind as was my manly massiveness, but the new Bonneville is certainly far more economical and efficient than the old. I wish I could say the same for myself.

It is also comfortable. The seat is firm, and the suspension (new 41mm Kayaba cartridge forks at the front and adjustable-for-preload Kayabas at the back with longer travel) is actually quite good.

Understand the Bonneville is not about high-speed corner carving; that said, it acquits itself well during spirited scratching with like-minded people. This is no fat-tyred cruiser that arse-steers its way around bends. The Bonny behaves like a well-balanced motorcycle should. It turns in much better than the old model, and holds its line with a good degree of precision, even if you find yourself in a gear higher than you should be.

It is highly geared, and sixth is a true over-dive. So it’s more tractable and enjoyable as a tourer than a scratcher. But it can be pushed quite hard if you’re that way inclined. There are good twin-discs up the front now, the chassis is heaps stiffer than the old one, and the rake is up 2.5 degrees.

I was actually more impressed with the new Bonneville than I’d thought I would be. It’s not just a styling exercise, though if that’s all it was, it would still be a success.

It is a great deal more sure-footed than I’d imagined, and the engine and gearbox are a great step up from previous models.

Is there a down-side? Not really, it is a beautifully-finished and competent motorcycle. But I guess it all depends on what you want out of your bike. Once you start heading north of 160, the Bonneville comes out of its comfort zone and if you’re really hooking into bends, you will find the ground clearance is a touch compromised. But as I said, you really need to be in a Death Race with other speeding madmen to find the Bonny’s limitations.

Around town it’s spot-on – all that bottom-end and mid-range torque and the great ergos make it delightful to ride from pub to pub and back to your girlfriend’s place. You could even take her with you, since I understand that pillion comfort is good, but given I only doubled the photographer to the top of the hill climb circuit, I cannot vouch for it.

It will also happily handle longer rides, so it’s an excellent all-rounder if you do some touring from time to time.

It sounds good, but interestingly, only to other people. The rider can’t really hear the muffled pea-shooter exhausts when he’s riding it. But you can certainly hear them when you’re behind one and it’s being feverishly downshifted to get around a corner.

So here’s a bike that has all the looks of a true classic, with all the good manners and smart technology we have come to expect today. It’s electronically sophisticated, but still pulls fully hectic wheelies when you turn that stuff off.

It is now the Bonneville it should have always been. Yes, you can put Thruxton cams in it. And yes, I am applauding.

It’s just a great shot.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY BENJAMIN GALLI

WHAT DOES IT COST?

The standard T120 and T120 Black are $17,000

The Bonnie T120 TT is $17,300 and the T120 Black PC (which is grey) is $17,200, presumably because it’s grey.

WHAT COLOURS CAN I HAVE?

The T120 Bonneville comes in Cinder Red or a glossy black called Jet. And that’s fine. But the two-tone Cranberry Red and Silver Aluminium is simply stunning, and surpassed in glory only by the two-tone black and white iteration, which is jaw-dropping.

The T120 Bonneville Black has been en-blackened even further for 2016, which is always the way forward. No, I do not know why Triumph made the seat brown. And I did ask.

It also comes in a slate grey colour, which is a light black, and looks quite Steve McQueen-jumping-barbed-wire-fences cool.

You may go HERE to look at the specs, check out the accessories and see more pretty pictures.