STARTING FIRST KICK

by Klink (written in 1980)

Six a.m. is no time to be hanging around Dover ferryport, on England’s South coast. Particularly when it’s raining. Nevertheless there I was, dripping in a rather roomy Motomod rain suit beside a stoical Ducati 900GTS, while assorted smug faces studied me with idle curiosity from behind the steamed up windows of their warm, dry cars. I ignored them and pondered what I would do about the Ducati’s push button petrol cap, which would release under the weight of my tank bag and drench the thing with gas.

Surprisingly, time passed quickly, perhaps because I was still half-asleep, and before I knew it various wet people were ushering me down the ramp and into the bowels of the Townsend Thoresen ferry. Once inside it was dry and clean. The steel deck was coated with special paint that provided adequate traction. A polite and dry person helped me tie the bike up to the side of the cargo bay, and I was off to the ferry’s cafeteria for a steaming hot coffee. An hour and a half later, right on schedule, I de-ferried in Calais, France.

It was still raining hard. I knew that I could expect a hot shower and a hot meal, (hopefully followed by hot sex) in my girlfriend’s house near Versailles, to the West of Paris. With these encouraging thoughts in mind, I blatted off into France. The route I had chosen was crowded with slow-moving traffic, so I turned off for the empty AutoRoute, having heard somewhere of a 40% reduction for bikers heading for the Bol D’Or. Of course the tollbooth troll hadn’t heard this rumour and charged me full fare. I ride on 31 francs poorer, vowing never to soil my wheels with AutoRoute again.

The GTS is behaving well, having loped 250 miles down the AutoRoute in heavy rain without missing a beat. Now weaving in and out of traffic on the Parisian ring road, the handling is cool and forgiving, the brakes Right There.

I arrive at 2p.m. local time, the garage doors of my girlfriend’s house opening in front of me as the syncopated beat of the bike’s exhaust bounces off the walls of the narrow village street. I ask my girlfriend how she knew I was coming. She taps the side of her nose like Asterix. What can I say? Nothing sounds like a Ducati!

In the morning I check the bike over. It is dirty but sound. I oil the chain and leave it. I don’t get away until after lunch, because everyone is so hospitable. Finally, with last warnings to ride safely, I set off southwards. The overcast sky holds and soon the Ducati is bowling down the N7 at 90mph. Nemours and Montargis are dwindling in my mirrors before my backside calls a halt. There is maybe one and a half inches of padding in the seat of a GTS. While this maintains a cool and ineffably Italian profile, it is not a luxurious butt park. There are still a good 550 miles to go, and I decide to try for Briare before stopping.

I’ve been keeping an eye open for other pilgrims and I suddenly come across a big UJM (Universal Japanese Motorcycle; a phrase popular in the ’70s and ’80s) parked on the hard shoulder. I spot the GB plate and pull up for a chat. A tall, lanky sort of bloke arises from the grass at the sound of the Ducati’s exhaust, valvegear, intake roar, bevel gears etc and comes over. A fellow Bol fan, it seems he had ridden down from Le Havre that morning, and stopped for a nap. For some reason it seemed perfectly reasonable to me for him to take a nap in the grass beside a main road. Man was tired.

We seem to get on OK and so agree to join up, although we never learned each other’s names. British reticence I suppose. Briare, Cosne and Nevers disappear behind, followed by Varennes, Roanne, and after a stop to pick up my new pal’s maps and tickets that had been blown out of his tank bag, St Etienne. It is now 5 p.m. We stop at an empty café on the mountain road and drink coffee while staring across a valley filled with pine trees. The sun shines. We grin at each other through the steam of our coffee cups. We know we’ve arrived.

Passing onwards and upwards, we soon find a gap in the wall of trees that lines the road and investigation proves this to be a good campsite, complete with a natural spring and sheltered from any wind. We make camp, which consists of erecting two tents and throwing everything inside them. During this process we discover that I’m Nick and he’s Keith. Once the tents are up we agree to eat out in the nearest village. Busy inhaling omelette and coffee, we are interrupted by the arrival of two more bikers, anonymous in leathers and full face helmets. Ah, the international camaraderie…

“Do you speak English?” asks the taller of the two, with shy belligerence. Bugger. But they’re nice blokes and after we’ve all finished eating, Keith and I offer to share our campsite. Night has fallen, and the four of us ride back into the dark forest. I wonder if we will be able to find the camp again. We do, and after some tea and some more talking we decide to get some sleep. It was a clear night and we were 2,500ft above sea level. Man it was cold! I’m rolled up in my el cheapo sleeping bag wearing everything except my boots and Bell Star and my teeth are chattering so hard I can’t hear myself sleep. (This night, recollected much later, helped me spend up on a terrific four season down bag for future camping.) At 6 a.m. I give up and get out to stamp around and make some coffee.

By nine we are all rolling under a cloudless sky, descending towards Toulon. The road winds down the hill and the Ducati drags me on faster and faster, with Keith and the others in pursuit. After a while it becomes clear that Someone Is Missing. We stop and wait. A truck passes, and as it does so the driver makes a graphic and final gesture. We look at each other in silence and then ride back up the mountain. Soon we come across our missing companion, slowly driving his Honda CX500 towards us. We all stop. It seems he just fell off trying to keep up with us. Keith mutters something about “bloody plastic maggots”.

Finally we all decide to go on, with the crestfallen CX500 pilot setting the pace. It is a slow pace and there seems to be always someone who wants to stop for gas, the bank or calls of nature. Keith and I seem to prefer more rapid progress, by a delta of around 30mph. The sunshine and the geography is distinctly Mediterranean now and even though it is mid-September, we start to sweat when we stop riding. We’ve stopped for a late lunch at a Routier. These are a kind of French transport café. Being French the food is excellent, unlike the English equivalent.

After lunch we ride on, with the understanding from our new friends that Keith and I may go ahead if the road gets interesting. Soon it does. Keith and I tussle on the dusty Provencal road. My memory of that time consists of blurring turn chevrons, hands and wrists aching with the effort of driving the bike and supporting my weight as I brake deep into the next bend; followed by that horizon-tilting, footpeg scraping swoop. Once with the feeling of a delirious two-wheel drift etched on my mind.

The last town before we begin to the climb the mountain to the Paul Ricard circuit is Aubagne, where we stop for petrol. The others catch us as we pull back onto the road. Then we get lost in the town’s poorly signed streets, filled with old and dusty French cars. Frustrating with the Paul Ricard mountain beckoning us on the horizon. Finally, we find the right road. I am in the lead and step the pace up to 70 to 80 mph. Keith passes me in a vortex of speed, as he works off some hot, sweaty impatience. I give chase, like Keith, seeing the road begin to wind sinuously as it rises towards the circuit. “Ace!” I think, “Ducati vs Honda, no contest”.

Keith looks in his mirrors, sees me breathing down his neck and opens the taps. Jee-zus, he’s moving! As I follow him around a large bend at an imprudent speed, I see a bike in the middle of the road, flames licking from its carburettors. It’s Keith’s Honda 750K2. I hit the brakes and pull up in a skid. As I leap off the bike, Keith runs up shouting for a fire extinguisher. I don’t have one. He is in an agony of frustration as he watches his bike and luggage burn up. He even tries to extinguish the flames with gravel from the side of the road. I talk him out of it.

By now a crowd of bikes has arrived. One rider even has an extinguisher, but it’s too late, the fire has too great a hold. All we can do is watch from a distance as the K2 burns more and more fiercely. Chain lube aerosols and Camping Gaz cylinders explode in the panniers and a pool of burning petrol spreads across the road. After about five more minutes a fire truck turns up, pretty efficient really, and quickly puts the fire out. A few fire fighters sweep the charred remains off the road. One sprinkles cement dust on an oil patch. Gendarmes direct traffic.

Along with the other two riders, I try and cheer Keith up. Physically he is OK, although his cheap leather jacket parted a seam on one sleeve, scuffing up Keith’s arm. But he’s lost practically everything: the bike’s an obvious write off, and with it his tent, sleeping bag, other camping stuff and clothes. Fortunately his passport and money are in a pouch on his belt. Keith recovers his composure quickly, and I snap a few pictures of him posing over the dead bike. “Pity you didn’t get any of the fire”, he says.

One of our two new friends has a tent that you could hold a circus in. He kindly offers to put Keith up for the duration of the race. After a chat with a surprisingly sympathetic gendarme we finally make it to the circuit. First impressions are noise and danger. There are literally thousands of bikers here. The Frenchies seem to think mufflers are for wusses. Everyone is trying to find a spot to camp or hurrying back to a place they saw earlier on the dusty dirt track around the circuit. Bedlam.

One of our two new friends has a tent that you could hold a circus in. He kindly offers to put Keith up for the duration of the race. After a chat with a surprisingly sympathetic gendarme we finally make it to the circuit. First impressions are noise and danger. There are literally thousands of bikers here. The Frenchies seem to think mufflers are for wusses. Everyone is trying to find a spot to camp or hurrying back to a place they saw earlier on the dusty dirt track around the circuit. Bedlam.

Eventually we get set up. Like a scene from Dumbo, we all work together to erect our friend’s marquee-like tent, then brew up. Keith finds some food in the blackened half pannier that is all he has been able to salvage from the wreck of his bike. Everything is covered in liquefied margarine. We eat. Keith explains that he took the bend hot, but not actually grinding anything, when he hit some oil and the rear “just went away”. From many people this would sound like bullshit. But Keith was good. (The following year we both went to racing school and Keith campaigned a season on a Yamaha RD350LC in the production series, but that is another story.) The crash is tough for Keith. His insurance is third party only, so it looks like he will lose it all.

Saturday is practice, prior to the start at 1500. We don’t have any food, so while Keith wanders down to the pits to hang with the racers, I take the Ducati into Le Beausset, the nearest town, to buy some food and beer. An official punches a star-shaped hole in my ticket and I’m back on the road. It’s back down the mountain to Le Beausset, and the winding road is temporarily part of motorcycle heaven; all the traffic is bikes. On the way down, everyone is playing racers. The Frenchies have all left their mufflers back at camp and their headers blare a song of youth as they blast down the hill, lean popping on the over run. Dozens of ecstatic riders going nuts in the sun. I spotted one set of twisted skid marks leading to an Armco barrier that looked like a fatal mistake for some poor bastard.

After loading up on bread, sausage, beer and tomatoes in a ‘supermarche’, the way back is just the opposite. Everyone is so bogged down with baguettes and wine that it’s a slow tortuous climb home.

By 1330 we are all set up on the free grandstand at the end of the half-mile straight. We drink beer, eat bread and cheese, and talk bikes. On the horizon we can just see the sun glittering on the Mediterranean. By 1445 the grandstand is full, the track is empty, and we’re going down with sunstroke. Typical English on holiday. Keith has had his arm painted orange by the free infirmerie, which is apparently doing a roaring trade, stacking up empty bottles of mercurochrome out the back like a bar on a Saturday night. Orange painted people are everywhere.

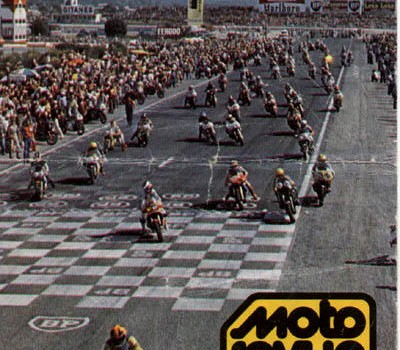

At 1500 exactly the race starts, but we can hear nothing except the excited yelps of the commentator. After a minute we can see them coming down the long straight towards us. Suddenly they are upon us and banking deep into the sweeping right hander. It’s a fight between the favourites, the works Honda team, and the upstart works Yamaha team, running OW31s and hoping they’ll last the distance. That’s one of the great things about endurance racing. You can run whatever you want. I watch the race for a while, but soon my head starts to feel bad, and I realise it’s time to make my own trip to the infirmerie. A pretty nurse in a blue jumpsuit gives me a lot of water, two aspirin and a cool cloth for my head. I joke with her about getting some part of me painted with mercurochrome, and she smiles and gives me a baseball cap for the sun. The cap has the ubiquitous Ricard logo on the front.

After supper we go for a walk around the circuit. It is dusk and the air is warm and fragrant with pine and Castrol R. Keith looks grotesque in his rolled up jeans and rolled down bike boots. His hairy white legs shine in the twilight. We pass tents, campfires and many bikes. Everywhere are happy Bol pilgrims, French, German, Italian and English, worshipping in the centre of their universe. All the while the howl of the race is like a choir, with the soprano two-stroke shriek of the OW31s, the alto wail of the fours and the bass thrum of the Ducati, Moto Guzzi and BMW twins.

We spend a lot of time at the end of the start-finish straight. There’s a particularly vicious ‘S’ bend there. We watched a young and unknown rider called Freddie Spencer on one of the works Hondas. Most riders would steer around the double bends without shifting on the bike, presumably in deference to the long race ahead. Not Mr Spencer. He would leap from one side of the bike to the other, literally pulling the bike over with him. This dramatic style provided appreciably higher speeds than the rest of the field, but must have been a lot more tiring. As we watched, Spencer’s Honda didn’t appear for a few minutes. When it re-appeared, co-rider Dave Aldanet was aboard. Keith and I exchanged looks. We knew he couldn’t last! As we walked on, neither of us had any doubt that we would be seeing a lot more of the young American with the works Honda ride.

Sunday dawned hot and loud. I checked my bike, which I had had to park some distance away from our campsite. I was relieved to find it still there, protected by its Kryptonite lock. It was covered in a millimetre of talcum-fine dust from the road. Its angular ugliness, primitive controls and wire wheels contrasted sharply with the glossily-styled battleships around it, like a praying mantis in a crowd of beetles. Oil mist covered the engine cases around the crankcase gaskets. Chain lube covered the rear wheel rim in sticky crap. The only shiny parts on the bike are the freshly scraped bevels on brake lever pivot and centre stand. I wonder, for the nth time, what I’m going to do about that stand. Since I’ve had the bike, I’ve hacksawed so much off it in the search for ground clearance that I can hardly hook it down any more. I’d remove it altogether, but the bike has no sidestand. Italians. Go figure.

There’s so much wrong with this bike, I don’t know why I put up with it. It’s hellish uncomfortable, ugly, awkward to kick over, and the battery keeps going flat. The switches and instruments are pathetic. Then I think of all the mistakes it has forgiven me: trying to catch up with Keith after being detained behind a lumbering caravan, I stuff the GTS into a long and bumpy sweeper. The stand grounds with a solid sounding graunch, and the peg starts to fold up, squashing my foot into the crankcase. I realise that I’m still not going to get around. Raising my foot I pull the duke further over. The grinding sound is threatening now and I can feel the metal starting to take weight. I pass a car with my head at door handle height and momentarily wonder if I’m looking good. Finally, I’m through and the big amiable GTS comes up so smoothly and responsively. I sense it laughing at my subsiding terror.

The memory makes me smile and I pat the bike surreptitiously. The end of the race is still three hours away, but I want to get back in the saddle. I say my good-byes to Keith and the others and pack my stuff. The Duke starts first kick and I’m rolling.

Getting on the road around 12:30, I spend the next twelve hours riding back to my girl friend’s place outside Paris, stopping only for gas and food. Even twenty years later I can remember that ride, heading north with the sun behind me, blasting down those French roads with the poplar trees strobing back on either side. I remember stretching at gas stations, hot strong coffee and baguettes eaten beside the road. That may have been the best ride of my life, but I live in hope.

EPILOGUE

The works Yamaha OW31s didn’t last, although one carried on for more than twenty hours. I think Spencer’s Honda team won. No Ducatis or BMWs finished. One Moto Guzzi finished, way down the order.

Keith made friends with a privateer team in the pits who, like many others, were campaigning a Z900 motor in a Peckett & McNabb frame. The crew kindly offered to take Keith and his bike back to England in their transporter. This was not a happy journey for Keith, as the crew passed a bottle of vodka around as they drove through the night back up to Dover.

Although Keith’s insurance didn’t cover him for his crash, he got a good price from a wrecker. He put the money towards a Rickman Honda, running a single cam gen-1 750 in a nickel-plated racing frame and AP brakes.

The Ducati’s flat battery was eventually traced to a loose coil in the alternator.

Keith and I kept in touch, and got together to ride to the Le Mans race the following Spring. I had sold the 900GTS by then for a Honda 900. I regret that sale the most, among all the trades I ever made.