FAMOUS MOTORCYCLISTS OF LAST CENTURY – PART X

Löof’s first ride: the 1926 Indian Scout 600

Löof Lirpå was born in Sweden in 1920.

His father Gustav, a reindeer skin rug manufacturer, lost his business in the Great Depression and spent his last few kroner moving his wife Irma and twelve year old Löof to the USA. He thought there would be more opportunities there. They arrived in 1932.

1932 and 1933 were the worst years of the Great Depression in America. Sweden, ironically, recovered fully from the Great Depression in 1934.

Some would say later that Löof inherited his incredible bad luck from Gustav.

Initially, Löof did well. He learned English quickly. He had a gift for languages, was a fine athlete and had an enquiring mind.

Löof fell in love with motorcycles at the age of fifteen, when Graeme Lever, an older (and wealthier) school friend bought an old Indian Scout. It had a 600cc V-twin motor, and like all Indians after about 1905, it was red. (Before 1905, they were all black and blue). Löof was hooked after his first ride.

He and Graeme were close friends, and Löof became close to Graeme’s whole family, so much so that they invited him to join them on a tour of Europe in 1937.

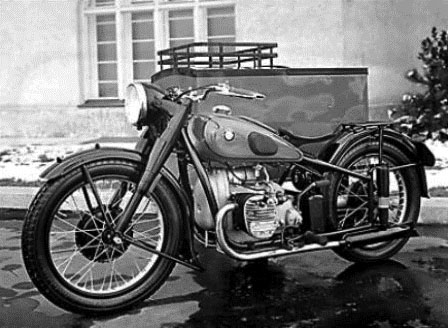

Löof’s first new bike: the 1938 BMW R61. BMW put rear suspension on its bikes for the first time in ’38. 600cc, 18bhp at 4800rpm, 4-speed box, telescopics front and back: 1,420 Reichsmarks. Löof got it a bit cheaper.

Löof was impressed with Germany, where the economy was starting to boom under the spending policies of the new National Socialist government. While he was there, he applied for (and won) a traineeship with BMW in their motorcycle plant at Eisenach-Durerhof in Eastern Germany.

Löof was looking forward to a promising career in the motorcycle industry. He started on 13 March 1938. That day Germany’s National Socialist government annexed Austria.

Seven months later, Löof had saved enough money to buy a brand new 1938 model R61 BMW. The day he bought it, Germany invaded Czechoslovakia. The factory where Löof helped build motorcycles was forced by the government to switch to building army trucks.

Milan-Tarente race in 1952: Francesco Laverda (left) and 3 official pilots: F. Diolio, N.Castallani and Lino Marchi. Löof didn’t think much of Francesco’s business plans.

Löof tried to leave, but the government regarded him as a worker essential to the war effort, and confiscated his passport.

Löof protested, so they confiscated his R61. They had ways.

Eleven months later, Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, France declared war on Germany, which scared Löof about as much as it scared anyone whom France declared war on. Then Britain declared war on Germany. Then Australia declared war on Germany. Then the USA declared war on Germany.

Löof stuck it out. He had no choice. In late 1944, the BMW factory at Eisenach-Durerhof was seized by the Soviet Army. BMW had abandoned the factory several days before the Russians arrived, and moved key personnel, including Löof, to their Munich factory, which made engines for fighter planes. Löof was promoted to Director of Production when the incumbent was drafted to fight the Russians on the Easern front.

The Guzzi V8 motor: Löof was hired to fix reliability problems.

Three months later, British Bomber Command levelled the Munich factory at night. Löof went in to look at the damage the next day, and while he was there, the US Air Force levelled the block of flats he was living in.

Löof was then broke and homeless, and lived on the streets for a while until the Allied armies took control of Germany. He drifted around Europe for a couple of years doing odd jobs. During one of these jobs (in a tractor factory in Italy) he met Francesco Laverda. Francesco and his brothers had recognized the need for cheap transport, and wanted to make a motorcycle.

Löof thought they were amateurs, who might have known about tractors but knew nothing about motorcycles. He was offered the job of production manager and a ten percent share of the company, but he turned it down.

The Laverda brothers incorporated their business the next year (1949), and made fine motorcycles until 2003.

Löof worked as a bartender for a couple of years, then applied for a job with Ducati. Ducati had just sold 200,000 Cucciolo mopeds, and were ready for something bigger. They hired Löof to manage production of the world’s first four-stroke scooter, which had been released at the Milan show in 1952. However, it didn’t sell, and after making a couple of thousand of them over two years, Ducati ceased production and laid Löof off.

Piece of piss, really.

His next job was still in manufacturing, but on a much smaller scale. Moto Guzzi had built a 500cc V8 Grand Prix bike in 1954. An Australian rider, Ken Kavanagh, had raced it at the Belgian Grand Prix, where it broke a crankshaft. They took it back and worked on it for over a year, and Ken Kavanagh raced it again in 1956, retiring with bearing problems. Löof was hired to bring his German-learned manufacturing skills to the troublesome engine.

Löof worked on it for a year, making changes to several key engine components. The machine won one race in 1958. It lost all the others to smaller and cheaper machines. Moto Guzzi withdrew from racing and laid Löof off.

Löof again took a while to get back into the industry he so loved. He moved to England and worked as a piano player at Poisson d’Avril, a high class Mayfair brothel, for a while. In his spare time he prepared a resume full of lies, and after shamelessly circulating it accepted an executive position with Associated Motor Cycles, the makers of AJS and Matchless motorcycles. He was sick of having short term jobs, and checked AMC out very carefully before accepting the job. Their published accounts showed a profit for fiscal 1960 of over 200,000 pounds.

Velocette had sporting bloodlines. As Löof was about to come on board, they released the machine below.

Löof took the job, and in 1961 they posted a loss of 350,000 pounds.

On the day he was laid off, he was the recipient of one of the few pieces of good luck in his life. His father’s brother, who had stayed in Sweden during the Great Depression, had bought into the paper industry cheaply and prospered. The old man had died and left a huge estate, of which Löof received a small share. The share might have been small, but the amount (over 500,000 pounds) was a fortune at the time.

Löof could finally afford to relax. He bought a flat in London. He spread the word that he was looking for investments. He met with some businessmen who were considering distributing the then-new Honda motorcycle range in Britain in 1962. Löof, however, had been burnt by small motorcycles before at Ducati, and decided against the investment. He was offered a controlling share of the Velocette motorcycle factory for 475,000 pounds, and shook hands on the deal.

The Velocette Viceroy did not appeal all that much to the traditional Velo buyer.

The 1961 Triumph T120 Bonneville: Löof’s last ride.

The week before he was to sign the deal, Löof purchased a brand new 1961 Triumph T120 Bonneville and decided he would spend a week touring Scotland.

He didn’t turn up to sign the deal with Velocette the following Monday, and it was a week before he was reported missing.

Scottish police finally found his bike. It was on its sidestand at the side of a Scottish lake called Loch Ness.

The keys were in it. The saddle bags were mounted. There was a puddle of oil under it. Löof’s helmet, his goggles, his gloves, a half empty packet of Players Silk Cut cigarettes and a Dunhill lighter with the initials LL engraved on it were found on the ground nearby.

The Triumph appeared to have blown a Zener diode.

There was no sign of Löof Lirpå.