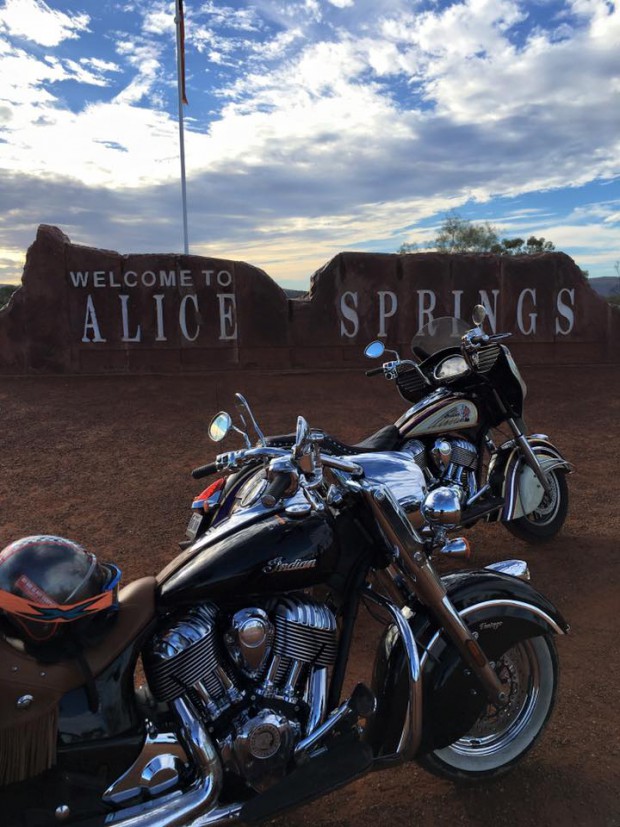

BACK TO ALICE – A FAST & FURIOUS ROCK FABLE

This is a difficult tale to tell, primarily because there are so many different components to it. There’s the ride itself, a 2800km odyssey from Sydney to Alice Springs over five days; in my case on two different bikes. Then there’s the Ian Moss factor, and what limitations occur when riding with a bone fide Aussie rock’n’roll icon, which was all done in support of the Black Dog Ride charity and as a promotional vehicle for the Indian motorcycle brand. And let’s not forget that this hurtling circus of worthies all ended up at the start of the Finke Desert Race; an amazing event which is in and of itself a tale of courage, conquest and commitment, but quite beyond the scope of this piece. So how do I tell such a story? Probably from the beginning; a beginning which was less than auspicious. But great bloody oaks do grow from little acorns…

“And the money I saved won’t buy my youth again”

“Come at me, Outback.” And it did.

As bits of Sydney were being reclaimed by the Pacific Ocean, and the entire east coast of NSW was being lashed like a screaming slave by a “significant weather event”, I presented myself at the Ashfield showroom of Indian and Victory, ready to ride to Alice Springs.

“What are you doing?” one of the Polaris execs asked as I was filling a Victory Magnum’s panniers (It was a carbon copy of the BikeMe!/Heavy Duty Project bike, but in stock form)

with my going-on-a-long-ride belongings.

“Packing,” I replied.

“You can just throw all that into one of the back-up vehicles, you know.”

“Cheers,” I nodded. “But I like to have all my shit all the time. You never know what may happen in the wilderness.”

“But we’re not riding today,” the exec advised me.

I stopped packing and looked quizzically at him.

“What are we doing then?

“We’re going to take the bikes to Dubbo on a truck and we’ll all hop on the Man Bus. Have you seen the Man Bus? It’s amazing.”

The Amazing Man Bus

I could have sat in one of these all the way to Dubbo…

…but I chose this instead. I regret nothing.

I had indeed seen the Man Bus, which was parked out front. And it was indeed amazing. It was matte black, pasted with promotional stickers, equipped with those fabulous swivelling leather armchairs and soft queen-sized beds. Its bar was being loaded with cases of beer as we spoke. When I was a teenager I used to dream about being on a bus just like it, travelling from gig to gig, with my band and an ever-changing succession of wet-mouthed groupies eagerly bolstering my status as a rock god.

But I haven’t been a teenager for a while.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “But I’m not getting on that bus.”

It was the exec’s turn to look quizzically at me

“This storm has caused flooding. Trees are down. Roads are closed. We have a duty of care to our customers and to Ian Moss. If something was to happen to any of them because we ignored this duty of care…”

He let that hang.

“Yeah, I get that,” I nodded.

And I did. Think about it. A major riding event by a major motorcycle manufacturer, augmented by serious star-power and big-time television coverage; and on the day it’s to leave Sydney, a thousand-bastard storm is taking place, and every plan that’s been made by Polaris has gurgled down the city’s over-flowing storm-drains. It was a tough call to make, but it was the right call for Polaris to make in these circumstances.

But it did not apply to me.

“Look,” I said. “I understand your position. You do have a duty of care to your customers, your staff and to all of rock’n’roll. But I am not a customer, I am not staff and I am sure not rock’n’roll. I’m the bloke you very generously invited along to tell the tale, and if I get on that bus and I don’t ride to Dubbo, that tale is not one I want to tell.”

He looked at me for a long time, and then he nodded.

“Fair enough,” he said. “Be careful.”

I went back to packing the bike and preparing my gear as Ian Moss arrived, along with Simon Bouda from Channel Nine and his camera crew.

A big, nervously smiling fellow in wet weather gear approached me. I had seen him roll up earlier on a loaded Hammer S.

“You riding?” he asked.

“I am.”

“Do you mind if I ride with you?” he said and stuck out his hand. “I’m Pat.”

“Nice to meet you Pat,” I said. “I don’t mind at all, but do not die, OK?

He blinked at that.

“I’m serious,” I said. “Do not die. Polaris will forgive me many things, but it will not forgive me if you die. So you have to promise not to die.”

“I promise,” Pat said.

And so Pat I set off for Dubbo, which was the first leg of our 2800km journey to Alice Springs.

This fire was less than ideal for my needs.

My erstwhile first-leg riding companion, Pat (left) and as much of Big Johnny Gee as I could fit into the picture.

Peter Harvey (left) is the General Manager of Polaris and Cameron Cuthill was our lead rider. Both of them think I am unwell in the brain.

“Build me up, tear me down, I won’t kneel ’til the trumpet sounds”

The rain was relentless all the way up to Mt Victoria, which was our lunch stop, and while the climb into the Blue Mountains required caution and demanded smooth throttle inputs, neither Pat or I came close to dying.

The Imperial Hotel hosted my gear in front of its little public-bar fire, and I found myself next to Ian Moss at lunch in the dining room out the back.

Being the embodiment of tact and diplomacy, especially when it comes to famous people, I searched for a suitable ice-breaker.

What does one say to a famous musician that hasn’t been said to him before, or without one sounding like a massive twat?

I had no idea.

One day, Ian Moss may write a song about the oppressive Hapsburg dynasty.

“Bet you’re sorry you’re not riding,” I finally stated through a mouthful of schnitzel.

“It would have been great to ride,” he grinned, then flicked a glance at the execs up the table. “But…you know…”

I nodded. Yeah, I knew. I understood why he wasn’t riding. I also understood it wasn’t his call. When you’re a living Australian rock treasure, your decisions are not yours to make. If there’s some chance you’ll be crushed under the wheels of a semi-trailer, alternative arrangements will be made.

So we talked about European history instead, and I started to see Ian Moss in a whole new way.

He is a quiet man – entirely unassuming and seemingly indifferent to his fame. His years and his astonishing talent sit easily on him. There is none of the rock god hauteur about him at all, but he is all about the music. He loves it, he creates it, and he performs it with a passion that cannot be denied. He is the real rock’n’roll deal, and by the end of lunch he shared my disdain for the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

While he posed for pictures with fawning waitresses, Pat and I geared up. The rain had eased off, but the roads were still wet and it was not warm. In fact, for the whole 2800kms to Alice, the temperature did not rise into the 20s, and spent most of its time struggling to get to 15. It was certainly winter.

The pub in Molong where Pat and I stopped for a bracing dram.

L to R: Kharen (Mick’s missus), the Molong pub’s bar lady, and Mick, who didn’t glass me when I spoke to him about the shame he had brought to his ancestors.

Pat and I stopped for a warming whisky in Molong, which is where I met Johnny Gee – an enormous German who sells vintage motorcycles in Melbourne, and Mick and his beaut wife, Kahran. All three had signed up for the ride, but were being bussed to Dubbo because they had assumed everyone else was being bussed to Dubbo. Had they known Pat and I were riding this morning, they would have insisted their bikes be taken off the truck. I know this, because I got to know all three of them quite well over the next six days, and I know that while they took my shit-stirring with good humour, the situation was hardly ideal.

“Perhaps you should all sit over there,” I said to them as they came into the pub. “Away from the people who have not shamed their ancestors by being driven to Dubbo.”

They laughed – which was good, because Johnny Gee is a metre taller than me and a genetic enemy of my people, and Mick had not long ago been a member of an outlaw motorcycle club. Either of them could have chosen to glass me about then. But instead they laughed, and I laughed, and Pat laughed, and then two of us geared up and rode to Dubbo.

That night, several miracles occurred.

“One week, two week, maybe even more,

piss all my money up against the damn wall”

Ian Moss played a killer concert at the most violent pub in NSW and no-one was stabbed or bashed, Valentino Rossi won the MotoGP at Barcelona, and the Polaris marketing girls beheld me doing a victory lap of the car-park in my underpants and did not call the cops.

Mossy gigs it in Dubbo to a select crowd of Black Dog Ride supporters.

And on the way outta town for photos and videos…

…which is, as you can imagine, a major production.

It requires the synchronisation of all communication devices.

All Andy and his matte black beast needed was to ride.

This lady rode hard, fast and happy the whole way.

I’ve actually seen him ride at 140-plus like this.

The next morning it was fine, but cool. All the bikes were off-loaded, all the riders (some 15 in all) geared up, and after some filming and photography of Ian Moss, the bikes, the bus and the road, we headed for Broken Hill.

Except for Mossy, who had to fly off to Queensland to play a gig and would rejoin us for the last leg from Coober Pedy to Alice Springs. The rest of us prepared for a big day in the saddle.

It is 758kms from Dubbo to Broken Hill, with only four petrol stops (Nyngan, Cobar, Emmdale, and Wilcannia), an old friend, and 1,765,453 wild goats to amuse me along the way.

Yeah, like you’re not gonna take a photo at THE Cobar sign.

Johnny White came for the blast to Cobar from just outside Dubbo. Just a short fang.

The friend was Johnny, the son of an old club brother of mine who passed a few years back. Johnny is the local ranger at Warren and when I pulled over just outside of Nyngan to hug him, he told me he was keen to ride to Cobar with me.

“Just take it easy,” he winked. “The two local Highway Patrols come out of Nyngan about nine. One comes this way and the other goes to Cobar.”

He was bang on the money. Ten kays out of Nyngan, at 9.05am, a Highway Patrol car came past us heading towards Dubbo.

After that it was game on.

The freight train rolls on.

Even Channel Nine was interested.

I had worked out a suitable compromise with Cameron, who was leading the ride.

“If you make me ride to Alice Springs at the speed limit, I shall go mad, and my outraged shrieking will haunt you until the end of days. I will even come to your house and self-harm in front of your pizza-delivery boy.”

“I have a duty of care,” Cameron intoned.

“I have a story to write,” I replied. “I cannot write it at 110km/h. No-one will read it. This is a creative issue and I will not have my creativity stifled by your nihilistic OH&S complications.”

“I know,” Cameron said. “But you understand that we do not condone any irresponsible behaviour.”

“Absolutely,” I nodded. “But I am a writer. Your condonings cannot apply to me according to the Magna Carta and the UN General Assembly Resolution 217A of 1948.”

“That’s the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, isn’t it?” Cameron blinked.

“It sure is,” I smiled.

He grinned back. “May the ghost of Boutros Boutros-Ghali watch over you.”

And so came we to Emmdale.

The vermin is large out this way.

The Cameron, rampant.

“Everything for miles is high on silence, everything’s my way.”

So out the front I went, and was quickly joined by Andy astride his matte grey Victory and Mick, piloting a black Chieftain. Clearly, there were other good men and true who were also not prepared to live under the condoning jackboot of an OH&S junta.

Thus did we wind on those big twins, and as herds of feral goats scampered from the thunder of our passing, we started knocking down the distance to Broken Hill.

The giant mined-metal sign of Cobar came and went, and our pause for petrol was brief. I said farewell to Johnny and 160kms of Mitchell Highway later pulled into Emmdale roadhouse for petrol.

I was served by a perky Belgian teenager, and had my burger cooked by an even perkier Spanish teenager. It would seem that backpackers can be found performing such duties all throughout the Outback, much to the delight of the local aboriginal roadcrew from Wilcannia, with whom I ate my food.

Mick watches. And waits.

Lots of sky.

And with so much sky, I took so much pictures of it.

“What are the cops like up ahead?” I asked.

“The local boys are OK,” said one of them. “It’s the Highway boys you gotta watch out for. And the emus.”

“Are there many between here and Broken Hill?”

“Yes, lots of emus.”

“No, Highway Patrol.”

“Some. But they seem to be spending their time booking people on the dirt roads lately.”

Good to know, I thought to myself. Andy, Mick and I applied ourselves to getting to Wilcannia, and were joined in our efforts by Johnny G, who was clearly exploring the upper reaches of his Indian’s top-end in the name of oppressed peoples everywhere.

The countryside was surprisingly verdant and unsurprisingly vast. There had been a lot of rain lately. The last time I was out this way it was a dustbowl, and I didn’t see many goats. Now the sides of the road were teeming with them. Happily, goats tend to run away from the road, so our speed was unaffected by their presence. I saw two emus and a kangaroo, but they were a fair way off.

Wilcannia. It all looks like this.

Then we were in Wilcannia. It’s a sad, hollow place. Bars cover every window. The streets are largely empty and the whole place feels muted and barren.

We had been warned not to leave our gloves or helmets unattended on the bikes, but since there were no people around or near the servo, I wasn’t too fussed. And we weren’t there long.

One of the reasons the four of us decided to ride as fast as we rode, was because we got to spend longer at the stops than the others did. This, in turn, made us happier, more rested and better disposed to our fellow man and the world in general. After all, Broken Hill was still almost 200km away, and none of us were yet acclimatised to such beastly distances. It takes a day or two to be able to blithely shrug off these 200-plus wild and empty kays between petrol stops.

Andy enjoys the vastness of it all.

Victory at Little Topar.

The second wave arrives.

This is probably why I pulled into Little Topar. It seemed like Broken Hill was just not getting any closer and it was coming on sundown and I wanted to take some photos. And I have at least seven other reasons why I just needed to stop doing 170km/h for a few minutes.

So I stopped, and Andy stopped, and Mick stopped. We got off our bikes and walked around a bit. We didn’t speak. We didn’t need to.

“I love the space out here,” Andy finally said quietly as the wind washed us and the outback engulfed us.

It’s like that out there. You either love it, or you’re so intimidated by the sheer size of the land around you and the sky above you, that you jump straight back into your car and never come back. But when you ride it on a bike, you cannot help but be immersed in the ancient immensity of Australia. It does not intimidate the motorcyclist, because you are not isolated from it as you are in a car. You are in it and of it. You become a transient, fast-moving fragment of it, and when you stop, you remain linked to it. A car driver steps out of his cocoon to behold the Outback. A motorcyclist cannot help but become a part of the very Outback he is riding through. The same wind anneals him.

Atop the slag mesa of Broken Hill.

The Sydney crew atop the slag.

Peter Alexander, CEO of Polaris, did some very big, very non-exec-type miles. Good on him.

Shortly afterwards, we were in Broken Hill (named after the Broken Hill Proprietary Company Ltd, or BHP Billiton as it’s now known), with its undulating intersections, its 20 pubs (there used to be more than 70), and the giant mesa of slag that dominates the town and comes from the largest single source of lead, zinc and silver ever discovered on earth.

That night, I slept the sleep of the red-wine infused desert-blaster. The next morning we were on our way to meet up with a contingent of Melbourne riders at Peterborough on our way to Port Augusta.

It was brisk and there’s not a lot of anything between Broken Hill and Peterborough, except the small whistle-stops of Cockburn, Mingary, Olary, Manna Hill, and our petrol stop at Yunta.

By this stage, Adam, Mick and I were spending more time looking at our petrol gauges than our speedos. We had decided that 160-180 was a comfortable touring pace, but that velocity meant we were needing petrol around the 200km mark.

And then back into big sky country.

And big truck country.

Engage Cruise Control and take photos. Breaks the monotony.

Mark Rholl smashing it out on a Scout.

Pat, still under his promise not to die.

I pushed the shutter button by mistake.

“You and I had our sights set on something. Hope this doesn’t mean our days are numbered”

But with full tanks, Mick and I engaged in a death-race the final 80klicks into Peterborough, and we found that the fairing arrangement on his Chieftain would give him a bit of a weave in 160km/h sweepers, whereas the Magnum I was on tracked sure and true every time. So the research aspect of our ride was addressed as well.

Yunta. It is interesting only because it has petrol and…

…it is the turn-off to this fascinating place.

In Peterborough, my beloved brother Neale Brumby and another 15 or so riders from Melbourne were waiting. I inhaled a steak and as we made for Wilmington and the winding descent of Horrocks Pass into Port Augusta, I discovered that Brum was also a fan of Human Rights. His custom Chieftain filled my mirrors, but when he stopped to take pictures on the pass, it was big Johnny Gee who sat in them through the twisties and past the caravans. For an enemy of my people, the big man was certainly not averse to Human Rights. A pair of roos slowed us down, but this did give me time to appreciate the astonishing view of the Spencer Gulf at sunset.

Peterborough was all about lunch…

…and rendezvousing with the Melbourne contingent.

Marc and Sandy.

Andy rides past the motorcycle museum with total disregard for history.

Port Augusta seemed to be almost entirely owned by a man called Ian. We walked past his chicken shop and ate in his pub.

The next morning we set off for Coober Pedy.

PLEASE BE ADVISED THAT PICTURES OF A KANGAROO THAT HAS BEEN HIT BY A MISSILE FOLLOW. THESE PICTURES ARE…UM, RED AND COLOURFUL. VIEWER DISCRETION IS ADVISED.

We were 40km short of Pimba when the roo kicked out of the scrub.

Tens of thousands of people have seen the pictures that were taken moments after the incident, and just as many have seen the video I shot on my phone with the goggle-marks still fresh on my face.

I have been accused of setting it up and I have been called a liar.

There’s not much I can do about that.

Johnny Gee cannot believe it. Neither can I. The photographer had just retrieved the chrome headlight from 400m back up the road.

It didn’t look too bad from the right side.

But that’s because all the serious stuff was on the left side.

This was the point of impact. Luckily, the strongest part of the bike.

The inside of the fairing just vomited the speaker covers out.

The only thing full of shit here was the roo.

My new Held Freezer II gloves are not so new now. It took some scrubbing to get the crap and meat out of them. Thankfully, they have great padding across the top, so my hand was only bruised and not broken when the speaker cover hit it.

But if you think for one second that me, Brum, Andy, Mick, Johnny G, and the marketing director of Polaris Australia, Adrian, along with the lead rider, Cameron Cuthill, and the two paramedics that accompanied us, Maria and Bob Holton, as well as the truck driver, Ray, all stopped on the side of the road, found some roadkill, then decided to drape it decoratively across the front of the Magnum, while making sure we scooped out its entrails and stomach contents, which we then flung up the side of my bike, onto my gloves and into my boots, and then kicked me in the spine, arse, both thighs, hand and shins to create bruises, while also remembering to smash up the front of the bike, you’re a dickhead of Outback proportions.

This is how it happened…

The kangaroo, a medium-sized Eastern Grey, came out of the scrub on my left. I didn’t see it until it came out on the road, and at 180km/h, there wasn’t a lot of time to do anything. So I didn’t. No brakes, just a reflexive bracing for impact. I hit it square and I hit it hard. The impact was massive and I felt it right through my body. I remember thinking: “Shit, I’m down!”

I’m thinking of making this my Facebook photo. It is, all things considered, rather epic.

Bob and Maria from Racesafe – just the best people to have your back.

“All around this chaos and madness”

But the Magnum just kinda shrugged. It had just copped a six-tonne impact (a mate of mine did the maths) directly on the bottom triple-tree and it just shrugged, and rolled on.

I pulled up four hundred metres from the point of impact. The stench was appalling. I was covered in roo shit and mince. There was pain in both my legs and my left hand throbbed. The speakers had popped out of the fairing and dangled, swaying on their wires as I idled to a stop.

Brum, who was directly behind me when it happened, pulled up next to me. He was pale and his eyes were like saucers.

The damage to Brumby’s Chieftain. Look closely, that is a big hit.

We exchanged a meaningful look. He couldn’t see my eyes through my goggles, but I’m sure they were as big as his. I should have been dead, or maimed. Or something. I certainly should not have been sitting upright on a motorcycle covered in warm kangaroo gizzards. It just didn’t compute.

As always, the truth is far stranger than any fiction.

“If you had just seen what I’d just seen,” Brum muttered, his face a mask of concern and horror.

“You should have seen what I saw,” I rasped back, my mouth gravel-dry.

I nudged the bike down from sixth into first, idled to the side of the road and got off. The pain in my legs was not getting any worse and I could walk, so there were no breaks. I pulled off my lid, goggles and face-sock. They were all flecked with gore and I smelt like offal. I have shot hundreds of roos, so the smell was not unfamiliar. But that didn’t make it any less vile. Thank the Road Gods the bastards are not carnivores.

By now, Johnny G, Mick and Andy had pulled up and were looking at me and the carrion draped across the front of my bike like it was some kind of impossible joke.

“You OK?” I was asked by everyone.

I nodded. “Yeah, I’m OK. My legs hurt a bit, but I’m OK.”

And I was. I shouldn’t have been. But I was.

Deconstructing it as my comrades photographed the result, and as the paramedics and the Polaris staff pulled up (they waved through the other riders, since we weren’t in a really good spot for 30-odd bikes to pull up, and no-one wanted this miracle to turn into a disaster), Brum, Johnny and I reckoned that the head had whipped around and corked my right thigh. One of the legs had hit me on outside of my left knee and drove my leg into the engine. The speaker had hit the top of my hand. The tail had arced around the front of the bike, broken the top of the left pannier and having expended some of its energy, went on to belt me mid-spine. The other leg had sheared off and taken out the bottom front edge of Brum’s fairing. We both felt it was fortunate it hadn’t speared him in the face.

More photographs were taken. I did a video and posted it on my Facebook timeline. Then the carcass was dragged off my bike and laid along the verge. It looked to be three metres long. I pissed on its head and called it names. It seemed rather fitting.

Cameron and Adrian wanted to know if I wanted to get into the bus, which was not far behind us.

“No, but thanks for asking. I shall continue,” I declared, as my legs throbbed and I actually wondered if was possible.

Right then. Fresh bike. More miles.

It was decided to put the wounded Magnum into the truck. On the side of the road, it looked like cosmetic damage, but it was impossible to know if there were any serious structural problems until it had been examined in more depth. Ray unloaded a spare Indian off his truck, and I set off for the Pimba roadhouse, grimacing under my stinking face-sock.

The stench was all-encompassing. I could not outride it.

I had become Roo-guts, the decayer of worlds.

By the time I rolled into Pimba, it had all dried, and people were staring at me. I don’t blame them. I was, in very real terms, a dead man walking. And I looked and smelled like shit.

Pimba roadhouse. That water is mainly from my washing.

Cameron and Johnny Gee very kindly helped me wash most of the dreck off using bore water from a hose on the edge of the roadhouse, while the other riders sailed off to look at the nothing that was the former Woomera missile range.

We all still had 370kms to ride before we got to Coober Pedy, and there was one special 255km stretch where we would have to nurse our petrol.

I sank into despair. This meant that I would have to ride at 100km/h for ages, with the stench of roo-bowels strong upon me. I couldn’t even eat my lunch at Glendambo. The lamb shanks smelled like marsupial, and people were still looking at me funny. I was limping and aching, and still entirely incredulous at my luck.

We filled our tanks to the very brim at Glenadambo and headed north. Polaris had made provision for the three Scouts and the back-up truck was carrying petrol. Mick prepared by buying a ten-litre fuel container, and Andy just looked at me accusingly. He had been robbed of the chance to race me to Coober Pedy for a bottle of good whiskey when I begged his indulgence after hitting the beast.

“Another time?” he’d asked.

“Another time,” I’d agreed.

He’d known it would have been a hollow victory.

None of these bikes has any petrol in them.

Road-side Selfie With Other Person No.1. Neale Brumby.

Road-side Selfie With Other Person No.2. Andy

Road-side Selfie With Other Person No.3. Mick

“Remember what they say, when you’re alone, laugh or die”

Now for those who have not ridden the Outback, let me assure you it is not entirely featureless and barren. Certainly, there are stretches of seeming nothing, but every now and then some stunning natural wonder will manifest itself. North of Port Augusta you will see vast lakes off to the west and east. Ancient volcanic cones rear from these lakes in spectacular fashion.

As you head north, impossibly old rock formations will randomly appear off to the side, while the road rises and falls almost imperceptibly, and the vista is always slowly, but irrevocably changing. Now and again you might even see a massive dead bullock swollen to twice its size lying beside the road, so that’s always a pleasant diversion from the geology.

The welcome is sparse, but the fuel is welcome.

And the vista is something else.

We all limped into Coober Pedy on fumes. Pat, who’d ridden with me out of Sydney and promised not to die, actually ran out of petrol at the town turn-off. I had slipstreamed Adrian for about 100km to make sure I made it. Secretly, I was pleased the pace had dropped. The gorgeous blue Indian Chief Classic I was now on certainly had the power to thunder along at 190, and it had a smoother engine than the Victory Magnum I had been riding. But I had removed the screen back at Pimba because it vibrates at speed and I was concerned I’d end up with epilepsy. And so I put in the truck and thereby made it not easy to hang onto the handlebars at the top end of the speedo. I also ached like a rotten tooth. But I found that if I rested my shins on the pillion pegs, it canted me forward enough to lessen the windsock effect, and thus I girded my man-panties and carried on.

Ian Moss. In a telephone booth. By a highway.

Best campfire ever.

Johnny Gee and Cameron Cuthill. Good men to do miles with.

That night, by a campfire, Ian Moss played a few songs, and Sandy, one of the blokes from Melbourne played a few songs. I stared at the fire, and chatted with Marc, a French-Canadian former soldier who had served in Somalia, Bosnia and Kosovo. He understood near-death experiences, was familiar with the land of my ancestors, and we shared a mutual loathing of the lying nanny-state.

But I needed to lie down in the worst possible way. I promised lead-rider Cameron I would not die in my sleep and limped off to my room.

My sleep was dreamless and deep. But I groaned like a wounded horse when I got up in the morning.

No matter. The end was in sight. It was only a short 690kms to Alice Springs. It’s funny how days of riding big distances tends to reduce those big distances to easily achievable jaunts.

Ian’s school mates rode south to Kulgera to catch up with him.

Finally, we behold the Territory.

The Finke ends somewhere behind this sign. ABout 100kms behind this sign.

I found these two at the border.

I found them again in Alice.

Ian Moss was now with us for the final leg, and while I had a brief flare of hope he would join the Human Rights activists at the front of the pack, and we would all hurtle into Alice screaming “Tucker’s Daughter” at the top of our lungs, it was all in vain.

The end of the ride.

He made it too, which was pretty good.

See? It’s not all flat.

Ian owns an Indian Chief Dark Horse, and he does ride. But he doesn’t ride much, and he freely admits it. So while we did our thing up front, he kept with the main group.

This trip back to Alice for him was fraught with meaning and quite poignant. He was born in Alice Springs, and he does get back from time to time, but it is rare. Ian has family there and many friends. Some of them even rode out to the Kulgera Roadhouse to meet him.

All promotional bullshit aside, Ian’s mum had passed not long ago, and one of the reasons he’d wanted to go back to Alice was to inter her ashes in his father’s grave. And he did just that.

What he also did was play a great gig at the scrutineering night of the Finke Desert Race.

Ian played a great gig at the Finke start line.

“Oh, who needs that sentimental bullshit, anyway”

Now without going into great detail, or rehashing what an utter and glorious monster Toby Price is for winning the race on his bike and piloting his Trophy Truck into second – a feat that actually quite beggars belief – I gotta tell you that if there’s one race you have to see, it’s the Finke.

What an absolute beast of an event. It is huge. The crowd numbers easily rival those of the MotoGP, and the only cops I saw were the ones in town keeping the backpackers safe. Out at the start line, volunteers did all the work – traffic control scrutineering, security, the lot.

And there is a lot to do.

More than 10,000 spectators camp along the brutal 230km track from Alice to the Finke River – a distance Toby rides in just one hour and fifty-three minutes. Yeah, do the maths.

Scrutineering is scrutinised.

Let us race in the desert like men.

All the gear all the time.

Tomorrow, I shall be handsome in the desert.

You be handsome. I be win.

It’s a there-and-back affair, with the competitors stopping for an overnight in Finke and then racing back. They also stop for fuel along the way (and these fuel stops are the best places to camp, I’m told). A fuel stop for blokes like Price takes about ten seconds. But not everyone who races is Toby Price. I spent some time in scrutineering and saw riders of all ages and all abilities pushing their bikes past the officials. Men over 45 get a race number starting with eight, presumably so the medical crews will know what they’re up against if it goes pear-shaped. After all, middle-aged bones are quite different to those of a 20-year-old.

The correct attitude for desert racing.

Tomorrow, I’m gonna roost the shit out of you.

Yes, promo girls. Of course, promo girls.

This year, KTM’s National Sales Manager, Tam Paul, took out the over-45s in a stunning display of “See? I’m not just a suit!” racing. He did the dash to Finke in two hours and 48 minutes, which is probably some 86 hours less than what it would have taken me, so good on him.

The feeling and the vibe of the Finke is incredibly unique. The competitors, from the $5000 shed-special riders to the drivers of the $500,000 Trophy Trucks with the V8 Supercar engines and gas-cooled suspension set-ups which look Klingon hell-cannon arrays, are all amazing. It is they who make the Finke such an astonishing event.

Shed-built specials run against…

…things that are plugged into computers…

…and have suspension like this.

And names like this.

My only regret is that I didn’t get to see any of it live. My job was to report on the ride Back to Alice, and I was on a plane and back to Sydney when girls were showing their boobs to Toby Price at Kilometre 138.

I am going back. I have to see the race. I have to behold this insane desert duel. We all do.

He’s actually 48-years-old.

Austria was well represented.

Meanwhile, up on stage.

Most of the ride group rode back to Sydney and Melbourne, leaving the day after I limped onto the plane. It was an epic ride for me, and certainly twice as epic for them, since they did twice the distance I did. I salute them. Top effort, blokes. And I am especially awed of Mick’s missus Kahran, who did the whole trip on a modified, unfaired Judge. Not once did she do anything but smile and smash out the miles. Except that second day in Alice when she also did Mick’s laundry.

At journey’s end, as we all sat in a bar in a fancy Alice Springs hotel, we were all smiling much the same as she was. We toasted each other, we toasted the journey, and we toasted Polaris for organising and so generously hosting us on such a vast trip.

We even toasted the bikes, all of which had been flawless. There were no loose nuts, no missing bolts, nothing had vibrated off and nothing had ceased to work. All we did was put petrol into them. I did put a kangaroo into mine, but the Magnum was rolling straight and true after the impact and I reckon I could have ridden it to Alice.

The Todd River carved its way through here.

Then it settled down.

I raised my glass with the rest of them, and I toasted the same things they all toasted.

And then I toasted the fact that I was still here to tell you the tale.

WHAT I WORE

Helmet – Nolan N21, which you can read about HERE

Jacket- Six-year-old Dainese winter jacket

Gloves – I alternated between two types of Held; the Freezer II HERE and the Air’n’Dry HERE

Pants – Held, with a review to come.

Thermal Vest – Held, with a review to come.

Boots – Six-year-old BMW touring boots

Face-sock – Oxford by Ficeda

Goggles – EKS brand, which you may read more of HERE

Vigilante thermal undergarments – The review is HERE

Big success.